Today, a considerable time after the Rav’s death, our sense of loss is every bit as acute as it was then—maybe even more so. Orthodoxy in America, while in some respects stronger today than in the Rav’s time, suffers every day from his absence. Issue after issue inflames passions and divides the community, while no voice speaks as the final authority for his constituency. Over the years, different people proclaim what the Rav did or did not stand for, drawing from their perceptions various lessons for decisions confronting Orthodoxy today. There is thus an intense struggle to keep the Rav alive so that he may continue to be our guide. I offer here some reflections on that struggle. Whereas the eulogies in the book [Mentor of Generations—Ed.] are retrospective, focusing on what the Rav was, this essay is prospective, as it focuses on what the future holds.

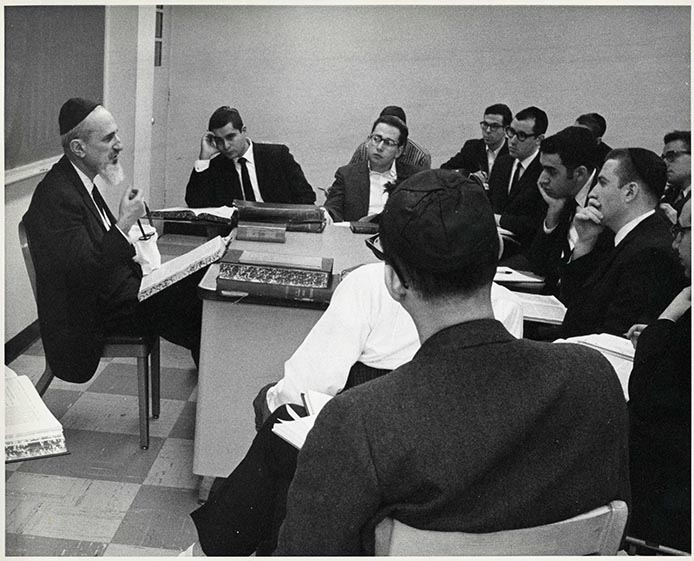

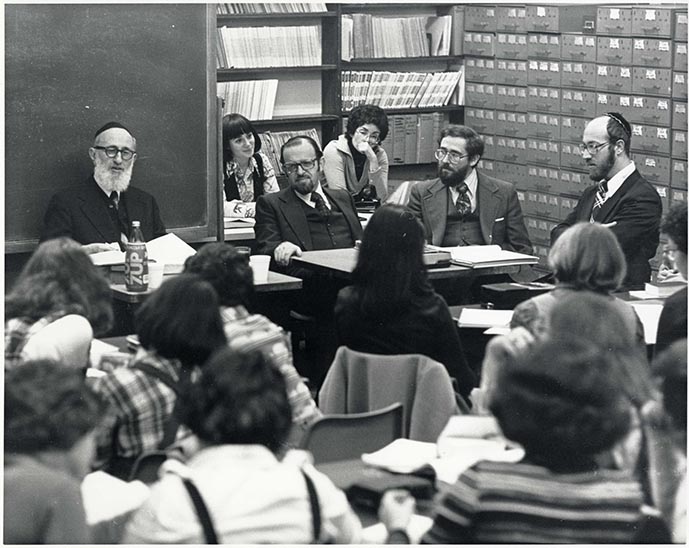

Many devotees of the Rav harbor a worry. To those who knew him or of him in his lifetime, the Rav, for all that he seemed larger than life, was a tangible, accessible and extraordinarily vivid presence. Memories of his voice, his dynamism, and the aura radiating from his shiurim are seared into our consciousness. It is very natural for us to wish that the next generation of students and leaders will maintain the same level of reverence, affection and attentiveness to the Rav as we do. But lacking the first-hand exposure we had, will they?

A very short time ago, to present someone as a 20th-century figure was to confer an aura of contemporaneousness, of relevance, of vibrancy and vitality, even if (like Rav Kook) the thinker had died well before mid-century. But what happens in 2020 or 2050? At that point, saying that someone lived in the twentieth century will date him, freeze him in time, rendering him a figure of a bygone era. In my generation, what the Rav said and did was news. For the next generation, it will be history. It will be a generation “asher lo yada et Yosef—who did not know Joseph” (Ex. 1: 8) in a personal, experiential way. They will not have a memory of the living presence we knew. Can we convey to another generation what the great figures of our generation represent?

This concern can only be exacerbated by the oft-heard claim that only those who knew the Rav on a personal level can understand what he stood for and how he thought. By stressing that the only way to understand him is through memories of his living presence, one implies that future generations cannot know him at all—surely a disheartening thought.

Such pessimism can and must be combatted. To begin with a small point, audio, video tapes and vivid photographs will help future generations relate to the past. But there is something far more fundamental: making personal contact a condition for understanding, appreciating and relating to a great figure contradicts one of the foundations of the Rav’s understanding of time and of the masorah.

The Rav distinguishes two ways a person can approach the past. One is to treat the past as dead and frozen, as no longer here. The other is to treat the past as something vital, flowing into the future, as a dimension that can come alive if we use it creatively. Time is not an insuperable barrier to knowing the sages of the tradition; with the right attitude, consciousness and sensibility, the past can be recovered.

The Rav often emphasized that despite the Halakhah’s emphasis on precise measurements of time, as in, for example, constructing the calendar and setting zemannei tefillah (times for prayer), our concept of a masorah is of a legacy that bursts through barriers of time.

Today, a considerable time after the Rav’s death, our sense of loss is every bit as acute as it was then—maybe even more so. Orthodoxy in America, while in some respects stronger today than in the Rav’s time, suffers every day from his absence. Issue after issue inflames passions and divides the community, while no voice speaks as the final authority for his constituency. Over the years, different people proclaim what the Rav did or did not stand for, drawing from their perceptions various lessons for decisions confronting Orthodoxy today. There is thus an intense struggle to keep the Rav alive so that he may continue to be our guide. I offer here some reflections on that struggle. Whereas the eulogies in the book [Mentor of Generations—Ed.] are retrospective, focusing on what the Rav was, this essay is prospective, as it focuses on what the future holds.

Many devotees of the Rav harbor a worry. To those who knew him or of him in his lifetime, the Rav, for all that he seemed larger than life, was a tangible, accessible and extraordinarily vivid presence. Memories of his voice, his dynamism, and the aura radiating from his shiurim are seared into our consciousness. It is very natural for us to wish that the next generation of students and leaders will maintain the same level of reverence, affection and attentiveness to the Rav as we do. But lacking the first-hand exposure we had, will they?

A very short time ago, to present someone as a 20th-century figure was to confer an aura of contemporaneousness, of relevance, of vibrancy and vitality, even if (like Rav Kook) the thinker had died well before mid-century. But what happens in 2020 or 2050? At that point, saying that someone lived in the twentieth century will date him, freeze him in time, rendering him a figure of a bygone era. In my generation, what the Rav said and did was news. For the next generation, it will be history. It will be a generation “asher lo yada et Yosef—who did not know Joseph” (Ex. 1: 8) in a personal, experiential way. They will not have a memory of the living presence we knew. Can we convey to another generation what the great figures of our generation represent?

This concern can only be exacerbated by the oft-heard claim that only those who knew the Rav on a personal level can understand what he stood for and how he thought. By stressing that the only way to understand him is through memories of his living presence, one implies that future generations cannot know him at all—surely a disheartening thought.

Such pessimism can and must be combatted. To begin with a small point, audio, video tapes and vivid photographs will help future generations relate to the past. But there is something far more fundamental: making personal contact a condition for understanding, appreciating and relating to a great figure contradicts one of the foundations of the Rav’s understanding of time and of the masorah.

The Rav distinguishes two ways a person can approach the past. One is to treat the past as dead and frozen, as no longer here. The other is to treat the past as something vital, flowing into the future, as a dimension that can come alive if we use it creatively. Time is not an insuperable barrier to knowing the sages of the tradition; with the right attitude, consciousness and sensibility, the past can be recovered.

The Rav often emphasized that despite the Halakhah’s emphasis on precise measurements of time, as in, for example, constructing the calendar and setting zemannei tefillah (times for prayer), our concept of a masorah is of a legacy that bursts through barriers of time.

The consciousness of halakhic man … embraces the entire company of the Sages of the masorah. He lives in their midst, discusses and argues questions of Halakhah with them, delves into and analyzes fundamental halakhic principles in their company. All of them merge into one time experience. He walks alongside Rambam, listens to R. Akiva, senses the presence of Abbayei and Rava. … ein mitah u-geviyyah be-haburat hakhmei ha-kabbalah, there can be no death and expiration among the company of the Sages of the tradition. … Both past and future become, in such circumstances, ever present realities (Halakhic Man, trans. Lawrence J. Kaplan [Philadelphia 1983], p. 120).

Who cannot learn from the Rav’s endearing memory in U-Vikkashtem mi-Sham of his days as a little boy, hearing his father give shiur in his home, when the Rambam would be surrounded by “enemies,” rishonim wielding weapons of logic to refute him? R. Moshe Soloveitchik would come to the rescue with a powerful sevara, to the delight of young Yosef Dov: “Father saved the Rambam!!” Look how alive Rambam was for him then and in all his later years. “Now too we are friends. … All the Sages of the masorah from Moses till today became my close friends. …” We know next to nothing of the Rambam’s one-on-one conversations, but we live with him through his writings. How could we engage Hillel or R. Akiva or Ramban or Rashba or R. Akiva Eiger as we do, if first-hand physical acquaintance were a prerequisite? Which individual who learned in the Rav’s shiur can forget how he brought rishonim and aharonim alive, so they were sitting right there, in that world unto itself, his classroom? The concept that temporal and spatial distances can be overcome lies at the heart of our masorah. The choice to leap across those distances, to bring the past into the present, to engage the writings of past masters so as to keep them alive—that choice is in our hands and those of our descendants. Divreihem hen hen zikhronam—the words of the righteous are their memorial, says R. Shimon ben Gamliel (Yerushalmi Shekalim 2:5). If we keep the Rav’s teachings alive, both his halakhic thought and his philosophy, we keep him alive for centuries to come. His teachings will keep him in the company of future generations. And so, realizing the nature of masorah as bursting through time can dissipate pessimism and lead to an energetic vitalization of the Rav in both Halakhah and mahashavah (philosophy).

The passage of time poses another challenge to those of us who want to see the Rav’s legacy perpetuated. As I’ve already implied, the Rav has left us two legacies—his Halakhah and his mahashavah. (I hasten to add that these must not be separated— he did more than anyone to bring them into a dynamic interaction). Talmudic and halakhic learning thrives today, but the world of mahashavah languishes. Already in his own time, the Rav felt that while his halakhic thought was being pursued passionately, his philosophy was largely ignored. It is obvious from the treasure trove of manuscripts that the Rav left at his death that philosophical works are an immense part of his legacy. He cared deeply that his students appreciate religious experience through philosophy. (See, e. g. Aaron Rakefett-Rothkoff, The Rav, 2: 238-241.)

Rabbi Yitzhak Twersky z”l has made the point that the Rav used philosophy as part of his intellectual capital, as an interpretive tool, and that the philosophy is a tzurah, a form, in which he couched his homer (literally, matter), i.e., his ideas (“The Rov,” Tradition [Summer 1996]: 28-33). But the nature of this interpretive process is clarified in The Lonely Man of Faith in a way that might lead us to pessimism:

Divreihem hen hen zikhronam—the words of the righteous are their memorial, says R. Shimon ben Gamliel (Yerushalmi Shekalim 2:5). If we keep the Rav’s teachings alive, both his halakhic thought and his philosophy, we keep him alive for centuries to come. His teachings will keep him in the company of future generations. And so, realizing the nature of masorah as bursting through time can dissipate pessimism and lead to an energetic vitalization of the Rav in both Halakhah and mahashavah (philosophy).

The passage of time poses another challenge to those of us who want to see the Rav’s legacy perpetuated. As I’ve already implied, the Rav has left us two legacies—his Halakhah and his mahashavah. (I hasten to add that these must not be separated— he did more than anyone to bring them into a dynamic interaction). Talmudic and halakhic learning thrives today, but the world of mahashavah languishes. Already in his own time, the Rav felt that while his halakhic thought was being pursued passionately, his philosophy was largely ignored. It is obvious from the treasure trove of manuscripts that the Rav left at his death that philosophical works are an immense part of his legacy. He cared deeply that his students appreciate religious experience through philosophy. (See, e. g. Aaron Rakefett-Rothkoff, The Rav, 2: 238-241.)

Rabbi Yitzhak Twersky z”l has made the point that the Rav used philosophy as part of his intellectual capital, as an interpretive tool, and that the philosophy is a tzurah, a form, in which he couched his homer (literally, matter), i.e., his ideas (“The Rov,” Tradition [Summer 1996]: 28-33). But the nature of this interpretive process is clarified in The Lonely Man of Faith in a way that might lead us to pessimism:

When the man of faith interprets his transcendental awareness in cultural categories, he takes advantage of modern interpretive methods and is selective in picking his categories. The cultural message of faith changes, indeed constantly, with the flow of time, the shifting of the spiritual climate, the fluctuations of axiological moods, and the rise of social needs (“The Lonely Man of Faith,” Tradition [Summer 1965], p. 64).

The separation proclaimed in this passage between the faith commitment and its cultural translation gives rise to an unsettling thought. The Rav’s philosophy plunges into intellectual controversies that raged during the 19th and early 20th century, but thereafter quieted, and it alludes often to philosophical schools whose day has passed. Much of his philosophical vocabulary is no longer in vogue. In other words, precisely because the Rav's philosophy is an act of "cultural translation," precisely because it is so exquisitely sensitive to the spirit of his times, his more technical writings stand in danger of losing, over time, some of their vitality and relevance. This is a paradox inherent in the genre of Torah ve-hokhmah or Torah u-Madda. We want thinkers to speak the language of their age. Yet the more a particular thinker's expressions of a Torah viewpoint are verbalized in the idioms and assumptions of his age, the more he takes account of his generation's needs and circumstances, the more he presents a union of Torah and cutting edge madda—the greater the danger that these expressions will eventually become dated and their enduring message lost. Add to this the facts that the Rav himself occasionally stresses the personal, subjective nature of his thought, that he prefers phenomenology (the description of religious consciousness) to logical argumentation on behalf of faith, and that he presents ostensibly contradictory viewpoints in different places— and the task of extracting stable and enduring lessons becomes intimidating indeed. In response let me point out, first, that the concern with obsolescence is about the Rav’s more strictly philosophic works and not about those works that are relatively free of technical philosophical vocabulary. The oft-quoted remark of Rabbi Arnold Jacob Wolf (writing in Shema, September 9, 1975) that “if I am not mistaken, people will still be reading him in a thousand years,” is true of works like Al ha-Teshuvah, even if there is a fear that other works may seem dated because of their less accessible vocabulary. More important, some rabbinic figures of the 19th century, for example, R. Samson Raphael Hirsch and R. Abraham Isaac Kook, flourished posthumously in the 20th, proving resonant and influential even though they too reflected themes and approaches of their times. Rambam is the most enduring writer in Jewish history, yet Guide of the Perplexed, and even parts of Sefer ha-Madda in the Mishneh Torah, are shot through with Aristotelian and Neoplatonic jargon and formulations. If Rambam traversed the temporal gap, it is because people found in him elements that transcend the particular context in which he wrote, so that those elements could be applied creatively in later times. Just so, what we need to do to perpetuate the Rav’s thought is to find its timeless messages. We must feel the duty to expound his works in the idiom of contemporary men and women. Such themes as the dialectical character of religious existence, the need to combine intellect with emotion, the ongoing battle against evil, and the Halakhah as a source of Jewish philosophy—these and many more ideas can be framed in universal terms that give them ongoing relevance. Historical studies of the Rav can also be of great importance. But we should develop such studies with an awareness of how a good history may address needs of the present. When R. Yitzhak Twersky z”l wrote history about Rambam or about law and spirituality in the sixteenth century in his capacity as a Harvard professor, he excelled at making the history contribute to an ongoing discussion. When a historian is skilled and thoughtful, he can make his subject relevant. It is to be hoped that histories of the Rav will not be written for history’s sake alone, but with the larger objective of conveying his teachings and establishing their continuing relevance. In emphasizing the need for spreading the Rav’s teachings, I do not mean to minimize a very different way of memorializing him: stories. He himself often used stories of personalities in the thick of his own philosophical explorations. In the period after the Rav died, I was struck by how much of the eulogizing of the Rav took place through storytelling. There were wonderful anecdotes about his charming relationship with first-graders in Maimonides; his concern for one of his shamashim (aides) who was going out on a date but didn’t have the proper socks; his hesed toward the Irish Catholic housekeeper who had come on bad times; his hosting a party for a member of the YU housekeeping staff; and much more. Why stories? The reason, I suspect, is twofold. First, the Rav was such a towering figure that we needed to remind ourselves of his deep humanity. Second, storytelling does not seek to display everything at once, a task that is simply undoable. Faced with the difficulty of articulating what this prodigious man stood for, we turned to glimpses. I would stress that the stories are valuable, not only because of what they say about the Rav’s humility and R. Hayyim-like kindness (R. Hayyim Soloveitchik was—as his matzevah attests— rav ha-hesed), but also because of the way they illustrate motifs of his philosophy. The story about his helping a first-grader who had been expelled from class because she didn’t know the Humash assignment illustrates beautifully, and concretizes, his words describing the Torah community: “The teaching community is centered around an adult, the teacher, and a bunch of young vivacious children, with whom he communicates and communes. ‘Yesh lanu av zaken ve-yeled zekunim katan ‘`We have an old father and a young child’” (Gen. 44:20). (“The Community,” Tradition (Spring 1978): 23.) Similarly, the many stories of the Rav’s own hesed reflect a theme that is utterly central to his thought concerning the Jewish value system, from his writings on Zionism to his endorsement of technology to his analysis of the nature of teaching. Hesed, he stated in an address to Maimonides school, is the password of the Jew. The stories bring out not only the person but the integrity, the unity, between the teacher and his teaching, ha-rav u-mishnato. Storytelling and philosophizing are not mutually exclusive; as the Rav did, we must bring these genres together. Indeed, precisely by fusing personal reminiscences with learned exposition, the eulogies for him brought out many dimensions of the Rav, and ultimately the wholeness of his thought and personality. The challenge of perpetuating the Rav’s legacy is great. But so is the opportunity to enrich generations to come. We need to engage his writings, extract the timeless messages in the time-bound parts of his oeuvre, and relate his biography to motifs of his thought. In this way we may see illustrated yet again that great principle of masorah: “There is no death and expiration among the company of the Sages of the tradition.” Dr. David Shatz, professor of philosophy at Yeshiva University and editor of the MeOtzar HoRav series, will present at YU's April 14 Day of Learning commemorating the Rav.