Dr. Nora Nachumi

Associate Professor, Department of English, Stern College for Women What is the worth of the novel in a world that revolves ever more around screens? This question lies at the heart of several courses I teach. One way to address it is to think about the qualities that belong to the novel: what is it, if anything, that makes the novel unique?

While the answers are various, mine has to do with the novel’s manipulation of the reader’s perspective. In the mid-1700s, when the novel began to be recognized as a distinct literary form, the quality that set it apart was its commitment to “formal realism,” a term coined by Ian Watt in The Rise of the Novel to describe the idea “that the novel is a full and authentic report of human experience” (32). Instead of classical models, novels took their inspiration from contemporary life. Their settings were concrete, specific and recognizable and their characters individuals instead of representative types. Films, of course, do this as well.

Novels, however, have the capacity to place the reader’s perspective inside the protagonist’s head. Passages that do so create the illusion that the reader has direct and unmediated access to the protagonist’s private thoughts and emotions. For a moment, the perspective of the character and the reader are close, if not one and the same. Frequently, these passages ask readers to register the difference between a character’s private, internal experience and the way that character appears in that particular scene. Film cannot invite viewers to experience this sense of “inside” and “outside” in quite the same way because it conveys all information through external signs.

This difference is evident if we compare a scene from the 1995 film adaptation of Jane Austen’s Persuasion (1818) with the original scene in the novel. In the film adaptation, the heroine, Anne Elliot, unexpectedly encounters her former fiancé, Captain Wentworth, while breakfasting with her sister, Mary. The sequence begins with short shots that convey the sudden, abrupt nature of the encounter. The camera zooms in on Anne’s face. . .

What is the worth of the novel in a world that revolves ever more around screens? This question lies at the heart of several courses I teach. One way to address it is to think about the qualities that belong to the novel: what is it, if anything, that makes the novel unique?

While the answers are various, mine has to do with the novel’s manipulation of the reader’s perspective. In the mid-1700s, when the novel began to be recognized as a distinct literary form, the quality that set it apart was its commitment to “formal realism,” a term coined by Ian Watt in The Rise of the Novel to describe the idea “that the novel is a full and authentic report of human experience” (32). Instead of classical models, novels took their inspiration from contemporary life. Their settings were concrete, specific and recognizable and their characters individuals instead of representative types. Films, of course, do this as well.

Novels, however, have the capacity to place the reader’s perspective inside the protagonist’s head. Passages that do so create the illusion that the reader has direct and unmediated access to the protagonist’s private thoughts and emotions. For a moment, the perspective of the character and the reader are close, if not one and the same. Frequently, these passages ask readers to register the difference between a character’s private, internal experience and the way that character appears in that particular scene. Film cannot invite viewers to experience this sense of “inside” and “outside” in quite the same way because it conveys all information through external signs.

This difference is evident if we compare a scene from the 1995 film adaptation of Jane Austen’s Persuasion (1818) with the original scene in the novel. In the film adaptation, the heroine, Anne Elliot, unexpectedly encounters her former fiancé, Captain Wentworth, while breakfasting with her sister, Mary. The sequence begins with short shots that convey the sudden, abrupt nature of the encounter. The camera zooms in on Anne’s face. . .

. . .before it pulls back to her standing beside Mary who is speaking to Wentworth.

. . .before it pulls back to her standing beside Mary who is speaking to Wentworth.

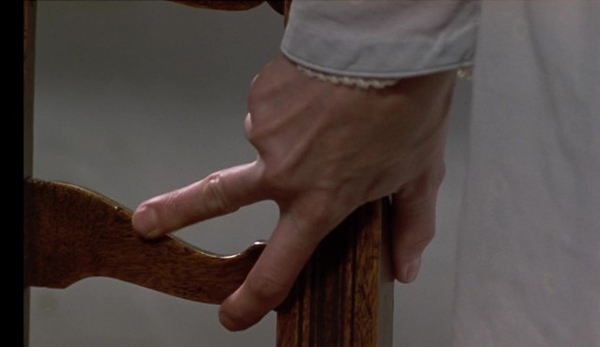

Finally, it gives us an extremely tight shot of Anne’s hand slowly tightening its grip on a chair.

Finally, it gives us an extremely tight shot of Anne’s hand slowly tightening its grip on a chair.

This is a powerful sequence, one that signals Anne’s distress despite her wooden demeanor.

In the novel, however, Anne’s inner turmoil is much more immediate. Austen achieves this effect through “free indirect discourse,” a literary technique that creates the illusion that we are somehow inside a character’s head.* In the following passage, the shift to free indirect discourse makes Anne’s confusion—her inability to do anything but feel her emotions—perfectly clear.

This is a powerful sequence, one that signals Anne’s distress despite her wooden demeanor.

In the novel, however, Anne’s inner turmoil is much more immediate. Austen achieves this effect through “free indirect discourse,” a literary technique that creates the illusion that we are somehow inside a character’s head.* In the following passage, the shift to free indirect discourse makes Anne’s confusion—her inability to do anything but feel her emotions—perfectly clear.

Mary, very much gratified by this attention, was delighted to receive him, while a thousand feelings rushed on Anne, of which this was the most consoling, that it would soon be over. And it was soon over. In two minutes after Charles’s preparation, the others appeared; they were in the drawing-room. Her eye half met Captain Wentworth's, a bow, a curtsey passed; she heard his voice—he talked to Mary, said all that was right, said something to the Miss Musgroves, enough to mark an easy footing; the room seemed full, full of persons and voices—but a few minutes ended it. Charles shewed himself at the window, all was ready, their visitor had bowed and was gone, the Miss Musgroves were gone too, suddenly resolving to walk to the end of the village with the sportsmen: the room was cleared, and Anne might finish her breakfast as she could. (85; emphasis mine)

From the moment Wentworth enters the room, the narrative focuses solely on Anne’s thoughts and sensations. It also conflates our experience with Anne’s. Like her, we receive information in fragments. Nor do we know what the others are saying. Meanwhile, the rhythm of the passage creates a sense of urgency. Nothing so dramatic exists in the film. The ability of narrative to wed our perspective to others is, I think, is the reason novels matter, even in a world dominated by screens. As the 18th-century philosopher Adam Smith observes in Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759), empathy is not automatically engendered by observation:Though our brother is on the rack, as long as we ourselves are at ease, our senses will never inform us what he suffers. . . . it is by the imagination only that we can form any conception of what are his sensations. . . . By the imagination we place ourselves in his situation, we conceive ourselves enduring all the same torments, we enter as it were into his body and become in some person the same person with him, and thence form some idea of his sensations, and even feel something which, though weaker in degree, is not altogether unlike them (9).

As viewers, our capacity to empathize with others depends on our willingness to go beyond what we see and hear: we must imagine both what characters feel and what we ourselves would feel were we in their position. As readers, we have less of a choice. Novels can manipulate our perspective so that we know what characters think and feel a semblance of what they themselves feel. The moral and practical possibilities engendered by these moments are enormous and hopeful. I also like to think that novels give us a way to conceive of ourselves and our world that is a useful alternative to the one provided by screens. Novels tell us that what we see—not only in films and television shows but on sites like Facebook and Instagram—is only the tip of the iceberg, that there is more to people, families and situations than meets the eye. As such, the perspective offered by novels may serve, if not as an antidote, at least as an alternative for those teenagers (and adults) whose self-esteem and connection with others largely depends on responses to their Instagram posts. Works Cited- Austen, Jane. Persuasion. The Oxford Illustrated Jane Austen, vol. 5, 1923.

- Dussinger, John. “The Language of Real Feeling: Internal Speech in Jane Austen’s Novels,” The Idea of the Novel in the Eighteenth-Century. Colleagues Press, 1998.

- Persuasion. Dir. Roger Mitchel. Screenplay. Nick Dear. BBC, 1995.

- Smith, Adam. Theory of Moral Sentiments. Clarendon Press, 1976.

- Watt, I. The Rise of the Novel: Studies in Defoe, Richardson and Fielding, Penguin, 1963.