Feb 23, 2019 By: pglassman

Happy Fair Use Week! Fair Use Week 2019 runs from February 25 through March 1 and promotes the awareness and significance of this valuable legal doctrine that provides the framework through which use may be made of copyrighted material without permission. This limitation on creators’ intellectual property rights promotes creativity and progress and safeguards our First Amendment right to free speech.

Examples of fair use are pervasive and integral to a flourishing society. Quoting, showing clips or images in news reporting and historical works, parodying, mash-ups and remixing, home taping of television programs, copying book chapters or articles for classroom use, and creating internet search engines are just a few. Academic libraries depend on fair use to copy non-textual materials for patrons to use for research, display thumbnail images of works in their library catalogs, reproduce materials for publicity and display, and much more.

Happy Fair Use Week! Fair Use Week 2019 runs from February 25 through March 1 and promotes the awareness and significance of this valuable legal doctrine that provides the framework through which use may be made of copyrighted material without permission. This limitation on creators’ intellectual property rights promotes creativity and progress and safeguards our First Amendment right to free speech.

Examples of fair use are pervasive and integral to a flourishing society. Quoting, showing clips or images in news reporting and historical works, parodying, mash-ups and remixing, home taping of television programs, copying book chapters or articles for classroom use, and creating internet search engines are just a few. Academic libraries depend on fair use to copy non-textual materials for patrons to use for research, display thumbnail images of works in their library catalogs, reproduce materials for publicity and display, and much more.

Judge Joseph Story

Judge Joseph Story All fair use images from Fair Use Infographic, commissioned by Association of Research Libraries, designed by YIPPA, licensed under CC BY

The importance of fair use to holders of primary source materials such as Yeshiva University Archives and our patrons is self-evident,

All fair use images from Fair Use Infographic, commissioned by Association of Research Libraries, designed by YIPPA, licensed under CC BY

The importance of fair use to holders of primary source materials such as Yeshiva University Archives and our patrons is self-evident,  however what may not be well known is that it was only relatively recently that the doctrine could be applied with confidence to the rich unpublished materials that archives generally hold. In contrast to the lengthy tradition of fair use that existed for published works described above, it was the accepted opinion that this did not apply to unpublished materials. This distinction originated in an author’s common law “first right of publication” of unpublished materials, which was considered absolute, as well as from concerns for privacy, which were deemed to outweigh any benefit to society of their disclosure. Additionally, since copyright in unpublished materials never expired (as discussed in a previous posting), the result was that these materials were, strictly speaking, fully restricted from any real use without permission from the rights holder.

however what may not be well known is that it was only relatively recently that the doctrine could be applied with confidence to the rich unpublished materials that archives generally hold. In contrast to the lengthy tradition of fair use that existed for published works described above, it was the accepted opinion that this did not apply to unpublished materials. This distinction originated in an author’s common law “first right of publication” of unpublished materials, which was considered absolute, as well as from concerns for privacy, which were deemed to outweigh any benefit to society of their disclosure. Additionally, since copyright in unpublished materials never expired (as discussed in a previous posting), the result was that these materials were, strictly speaking, fully restricted from any real use without permission from the rights holder.

As a practical matter, however, scholars did, for example, cite from unpublished materials despite not having fair use to do so, and archivists likewise did make copies of materials for researchers for their private use. Even the National Archives funded copying to microfilm of its and other repositories’ holdings. All of these were, per the letter of the law, violations of the rights of authors or their heirs. These widespread practices were deemed necessary in the face of copyright laws that were out of date with modern scholarship practices (especially the “new” technologies of microfilming and fast photocopying). Without statutory protection or penalties, however, there generally was little risk from these activities, as rights holders could only sue for actual damages. Still, these practices did not have the force of law.

As a practical matter, however, scholars did, for example, cite from unpublished materials despite not having fair use to do so, and archivists likewise did make copies of materials for researchers for their private use. Even the National Archives funded copying to microfilm of its and other repositories’ holdings. All of these were, per the letter of the law, violations of the rights of authors or their heirs. These widespread practices were deemed necessary in the face of copyright laws that were out of date with modern scholarship practices (especially the “new” technologies of microfilming and fast photocopying). Without statutory protection or penalties, however, there generally was little risk from these activities, as rights holders could only sue for actual damages. Still, these practices did not have the force of law.

The 1976 Copyright Act was initially believed to have provided this much-needed relief to the scholarly community by extending federal copyright protection to unpublished materials, against which the claim of fair use, also codified in the Act, could now be made. However, rulings in several influential early court cases not only seemed to undermine any gains, but also gave rise to a trend that threatened to curtail the use of unpublished materials beyond what had existed even before the Act’s passage.

One such early case was Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc. v. Nation Enterprises, in which Harper, the publisher of President Gerald Ford’s memoirs, sued Nation Enterprises for making use of a purloined copy of the work to print an article revealing salient portions of its contents shortly before the book was published in 1979. The case was ultimately argued before the Supreme Court, which denied The Nation’s claim of fair use. Its ruling was based in part on the fact that the excerpted portions were still unpublished at the time they were used, which it said leaned against a finding of fair use. The Court also stressed the primacy of authors’ right to benefit financially from their work, evocative of the ‘first right of publication’ inherent in unpublished material from the pre-fair use, common law era.

While publishers rejoiced over this ruling, they and the overall scholarly community were dismayed by others that followed during

The 1976 Copyright Act was initially believed to have provided this much-needed relief to the scholarly community by extending federal copyright protection to unpublished materials, against which the claim of fair use, also codified in the Act, could now be made. However, rulings in several influential early court cases not only seemed to undermine any gains, but also gave rise to a trend that threatened to curtail the use of unpublished materials beyond what had existed even before the Act’s passage.

One such early case was Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc. v. Nation Enterprises, in which Harper, the publisher of President Gerald Ford’s memoirs, sued Nation Enterprises for making use of a purloined copy of the work to print an article revealing salient portions of its contents shortly before the book was published in 1979. The case was ultimately argued before the Supreme Court, which denied The Nation’s claim of fair use. Its ruling was based in part on the fact that the excerpted portions were still unpublished at the time they were used, which it said leaned against a finding of fair use. The Court also stressed the primacy of authors’ right to benefit financially from their work, evocative of the ‘first right of publication’ inherent in unpublished material from the pre-fair use, common law era.

While publishers rejoiced over this ruling, they and the overall scholarly community were dismayed by others that followed during  the 1980s. In Salinger v. Random House, Inc., a biographer was prevented from quoting or even closely paraphrasing letters by J.D. Salinger. The decision again emphasized the unpublished nature of the letters. An even more alarming ruling was New Era Publications International v. Henry Holt and Co., in which the Church of Scientology wished to prevent use of unpublished materials in Bare-Faced Messiah, a work that disputed its founder L. Ron Hubbard’s account of events. In contrast to Salinger, where making use of the creator’s material was primarily for literary and stylistic purposes, here it was to in order to provide criticism and commentary, which are foundations of a democratic society and even examples listed in the Copyright Act as purposes favoring fair use. While the case was dismissed on a technicality, an appellate ruling strongly implied it would have otherwise succeeded, noting "fair use is never to be liberally applied to unpublished copyrighted material, even if the work is a matter of ... high public concern."

As a result of rulings such as these, the scholarly community essentially found itself in a worse position than it was before passage of the 1976 Copyright Act with regards to using unpublished materials.

the 1980s. In Salinger v. Random House, Inc., a biographer was prevented from quoting or even closely paraphrasing letters by J.D. Salinger. The decision again emphasized the unpublished nature of the letters. An even more alarming ruling was New Era Publications International v. Henry Holt and Co., in which the Church of Scientology wished to prevent use of unpublished materials in Bare-Faced Messiah, a work that disputed its founder L. Ron Hubbard’s account of events. In contrast to Salinger, where making use of the creator’s material was primarily for literary and stylistic purposes, here it was to in order to provide criticism and commentary, which are foundations of a democratic society and even examples listed in the Copyright Act as purposes favoring fair use. While the case was dismissed on a technicality, an appellate ruling strongly implied it would have otherwise succeeded, noting "fair use is never to be liberally applied to unpublished copyrighted material, even if the work is a matter of ... high public concern."

As a result of rulings such as these, the scholarly community essentially found itself in a worse position than it was before passage of the 1976 Copyright Act with regards to using unpublished materials.  While offenders had previously faced minimal damage claims in cases that were seldom brought, creators could now bring to bear the much greater weight of a federal statutory violation in support of their claims. Coupled with a legal environment that seemed predisposed against a fair use defense, unpublished materials began to be considered too toxic for any meaningful use. Publishers were warier of permitting them in works, and some works could not be published at all. In some instances, archivists hesitated to make their collections available. The chilling effect on scholarship was notable and of much concern.

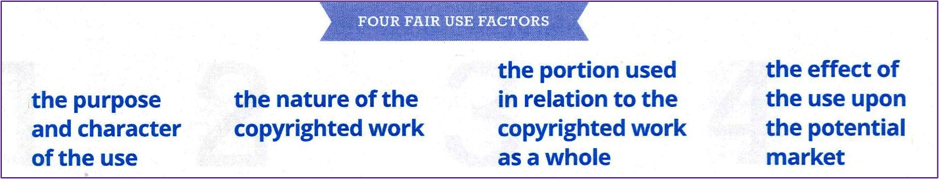

The outcry from historians, biographers, librarians, archivists, journalists, scholarly presses and others demonstrated the need for a statutory remedy, and legislation was passed by Congress in 1992 amending the Fair Use section of the Copyright Act. After listing the four factors it added “the fact that the work is unpublished shall not itself bar a finding of fair use if such finding is made upon consideration of all the above factors”. The Amendment’s intent was to remove the courts’ predisposition against fair use with regards to unpublished materials, and based on cases adjudicated in its aftermath, it became clear that it had been effective. The lockbox into which unpublished materials had been placed was opened.

While offenders had previously faced minimal damage claims in cases that were seldom brought, creators could now bring to bear the much greater weight of a federal statutory violation in support of their claims. Coupled with a legal environment that seemed predisposed against a fair use defense, unpublished materials began to be considered too toxic for any meaningful use. Publishers were warier of permitting them in works, and some works could not be published at all. In some instances, archivists hesitated to make their collections available. The chilling effect on scholarship was notable and of much concern.

The outcry from historians, biographers, librarians, archivists, journalists, scholarly presses and others demonstrated the need for a statutory remedy, and legislation was passed by Congress in 1992 amending the Fair Use section of the Copyright Act. After listing the four factors it added “the fact that the work is unpublished shall not itself bar a finding of fair use if such finding is made upon consideration of all the above factors”. The Amendment’s intent was to remove the courts’ predisposition against fair use with regards to unpublished materials, and based on cases adjudicated in its aftermath, it became clear that it had been effective. The lockbox into which unpublished materials had been placed was opened.

As a right that belongs to everyone, fair use is something to be broadly celebrated this week, but perhaps especially so by those interested in unpublished materials, which it neither equally nor equitably applied to before the 1992 Amendment. Yeshiva University Archives has numerous collections with unpublished materials in its holdings of personal papers and institutional records. We invite you to make fair use of them this week and every week!

Posted by Deena Schwimmer, Archivist

As a right that belongs to everyone, fair use is something to be broadly celebrated this week, but perhaps especially so by those interested in unpublished materials, which it neither equally nor equitably applied to before the 1992 Amendment. Yeshiva University Archives has numerous collections with unpublished materials in its holdings of personal papers and institutional records. We invite you to make fair use of them this week and every week!

Posted by Deena Schwimmer, Archivist