Mollie Sharfman

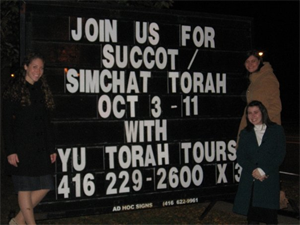

Mollie Sharfman Mollie Sharfman (bottom left) on Torah Tours

Mollie Sharfman (bottom left) on Torah ToursAnd then Mollie S. talks about her grandfather, with whom she has a close relationship. He was the first to hold her in his arms after she was born. “He always wanted to protect me from all evil,” she says. The grandfather lost his whole family, more than 100 relatives, in the Holocaust. Because of the events in Halle, she now feels a special connection to her family. “I feel like a survivor now, too," she says. And then she takes a piece of paper out of her pocket; on it is a prayer with which her grandfather always blessed her with tears on the eve of Yom Kippur, as she says. She reads it in Hebrew and English: “May God bless and protect you / May God show you favor and be gracious to you / May God show you kindness and grant you peace.” When Mollie S. says the prayer, it is completely silent in the courtroom. It is as if all of the dead from her family were suddenly sitting in the room.

Mollie with her grandfather, Chazzan Joseph Guttman z”l

Mollie with her grandfather, Chazzan Joseph Guttman z”lApplause in the courtroom is considered inappropriate. But it does happen once, after acquittals, for example. Applause after questioning a witness is unusual. But that's exactly how the eighth day of the trial in the trial of the right-wing extremist attack in Halle begins, when the co-plaintiff Mollie Sharfman freed herself from the assailant's power on the witness stand. Mollie Sharfman is the first voice in the trial of the Jews who visited the Halle synagogue while the perpetrator tried to gain access to the building. Sharfman speaks calmly and deliberately past the perpetrator into the room and yet tells the 28-year-old right-wing extremist: “You messed with the wrong person, with the wrong family, with the wrong co-plaintiffs. You messed with the wrong people. From that day on, he will no longer cause me personal agony. It ends today.”

As she said in an interview with DW, “This attacker—this person who is filled with so much hate—he cannot take away what my grandfather taught me, what my grandfather gave me. So, that’s what made me feel the strongest was this connection with him. And I felt it was important to share that in the court. That is resilience.” In the months since the trial, many thoughts have crossed her mind, not all of them neatly fitting one into the other. For instance, “this still doesn’t fit in with my narrative. I don’t fully accept that this happened to me. This is not how the story is supposed to go. My grandfather survived the Holocaust, we’re supposed to be safe, anti-Semitism is not supposed to be a problem that we, as a Jewish people still have (even though it is increasing in Europe and America). I don’t know what it means to ‘accept,’ what it looks like.” Yet, she is acutely aware of the outward ripple effects of an incident like this. “The number of people who are affected by something like this is not just the ones affected immediately—the woman he shot, the nurse walking by the wounded woman who tried to help her, the taxi driver he assaulted, the young man killed in the doner shop and his devastated family. He targeted one group but ended up hitting everything. So many people will forever be affected by this hate crime.” What she hopes to achieve is a state in life where “I am able to do the very opposite of what the attacker tried to do: to do work that achieves a positive ripple effect across the Jewish community and the world.” “On the one hand, I feel empowered— I stood up to someone who is filled with so much hate—and on the other, it’s just one of those things that I bring up or not, depending on the situation.” She doesn’t want to be defined as “Mollie who was in a terrorist attack,” but she also knows that it will be something that will always shade her responses and the routine facts of daily living. “G-d willing, I will live a very happy and fulfilling life, living in my values, and this will only come up every so often. That is what I hope.” For more of Mollie’s thoughts, read an account she wrote in The Jewish Week and an article for in the BBC, listen to a speech she gave outside the courtroom after her testimony and listen to excellent interviews with DW and BBC Radio.