Aug 11, 2020 By: yunews

By Dr. Ronnie Perelis

Chief Rabbi Dr. Isaac Abraham and Jelena (Rachel) Alcalay Chair in Sephardic Studies

Associate Professor of Sephardic Studies

Director, The Rabbi Arthur Schneier Program for International Affairs

On July 27, 2020, I taught a class—nothing unusual for a professor in that. Except that during this class, on the period from the anti-Jewish riots of 1391 to the expulsion of the Jews in 1492, 500 people from Chile, Panama, Mexico, Miami, Tetuán and Caracas, to name just a few of the places, joined me through the Zoomisphere as I sat in my basement, my bookshelf behind me, wearing a suit (but keeping my sandals on). I was invited to teach this class by Rabbi Marcos Metta, a dynamic rabbi in Mexico City whom I had the honor to meet on a research trip to that sprawling megalopolis a few years back. I had taught at his synagogue in the leafy suburb of Lomas and had met a diverse, curious crowd of adult learners as part of his innovative Beit Midrash, Majón Torá veDaat. From the questions I was asked I could tell that the people on the call from all over the Americas were smart, well-educated and passionate participants. In signing on to this class about medieval Spain, these participants were strengthening their Diasporic ties while linking themselves back in time to a crucial and often misunderstood chapter in their communal formation. And as the president of FeSeLa (Federación Sefaradi Latinoamericana), one of the class’ organizer’s said, this was the first time that so many communities were able to share this singular experience. But…

But I missed hearing their voices, seeing their faces, being in the same room sharing pastries and coffee after the lecture, joining a minyan for arbit [evening prayer] right after the class, listening to a mourner say the Kaddish [prayer of mourning] for their loved one, noticing who joined and who sat out this act of public piety.

I missed the little things, missed people in the flesh, even missed the mishaps along the way: the traffic on the way to the community center, the rain that keeps people away.

But…

But with all my sense of loss, I must also admit that this Zoom thing is pretty miraculous because it allows Diasporic communities to highlight and live their connections “in real time.”

For centuries different Diasporic groups maintained their identity despite their geographic and political separations through trading networks, bonds of marriage and shared customs and religious beliefs. But these ties were maintained through the traffic in letters, goods, money and people. It also took patience for that letter, or that shipment of pepper, or the groom to arrive, and so it took imagination to maintain that sense of cohesiveness that linked people across the seas and mountains and empires that separated one member of the group from another. Zoom allows us to create and keep those bonds immediately and all at the same time.

Here’s another example. This spring, in collaboration with the American Sephardi Federation, I was involved in Zoom events linking scholars, hazzanim [cantors] and passionate members of the western Sephardic diaspora. These events came out of a landmark international research conference that had been scheduled for early May, called the Global Nação, referring to the global network of trade and faith that linked the western Sephardim from Amsterdam to Curacao to Livorno to Jamaica to New Amsterdam.

The conference was part of the Diasporas Project at the Rabbi Arthur Schneir Program for International Affairs, a multi-faceted series of events exploring the connections that cross political and geographic divides in our globalized world.

We obviously could not have the conference, but we decided to host a mix of communal and scholarly programs. The first was a musical tour of cantorial music with hazzanim from Tuscany, Amsterdam, Bayonne, London and New York, giving us a look at the variety and commonalities of this musical tradition that has remained vibrant across time and space.

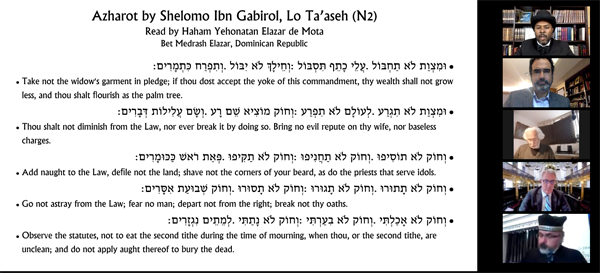

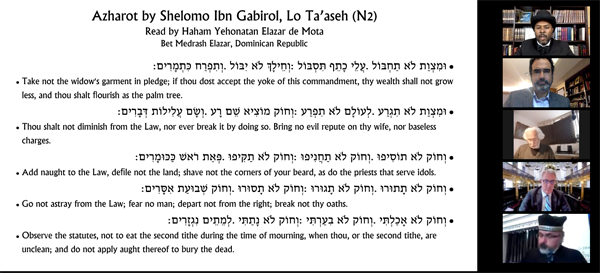

A week later, with the organization and vision of Zachary Edinger of Congregation Shearith Israel there was a monumental gathering of hazzanim from communities in Europe and the Americas, each singing a part of the classic Azharot [liturgical poems recited on Shabuot]. We also had a panel of authors—Laura Leibman, Stanley Mirvis and Hillit Surowitz-Israel—with new books coming out right now about the Jews of the Caribbean. COVID may have changed the nature of the book tour, but at least we were able to get these authors together for a serious conversation about race, religion and the writing of history.

But…

But I missed hearing their voices, seeing their faces, being in the same room sharing pastries and coffee after the lecture, joining a minyan for arbit [evening prayer] right after the class, listening to a mourner say the Kaddish [prayer of mourning] for their loved one, noticing who joined and who sat out this act of public piety.

I missed the little things, missed people in the flesh, even missed the mishaps along the way: the traffic on the way to the community center, the rain that keeps people away.

But…

But with all my sense of loss, I must also admit that this Zoom thing is pretty miraculous because it allows Diasporic communities to highlight and live their connections “in real time.”

For centuries different Diasporic groups maintained their identity despite their geographic and political separations through trading networks, bonds of marriage and shared customs and religious beliefs. But these ties were maintained through the traffic in letters, goods, money and people. It also took patience for that letter, or that shipment of pepper, or the groom to arrive, and so it took imagination to maintain that sense of cohesiveness that linked people across the seas and mountains and empires that separated one member of the group from another. Zoom allows us to create and keep those bonds immediately and all at the same time.

Here’s another example. This spring, in collaboration with the American Sephardi Federation, I was involved in Zoom events linking scholars, hazzanim [cantors] and passionate members of the western Sephardic diaspora. These events came out of a landmark international research conference that had been scheduled for early May, called the Global Nação, referring to the global network of trade and faith that linked the western Sephardim from Amsterdam to Curacao to Livorno to Jamaica to New Amsterdam.

The conference was part of the Diasporas Project at the Rabbi Arthur Schneir Program for International Affairs, a multi-faceted series of events exploring the connections that cross political and geographic divides in our globalized world.

We obviously could not have the conference, but we decided to host a mix of communal and scholarly programs. The first was a musical tour of cantorial music with hazzanim from Tuscany, Amsterdam, Bayonne, London and New York, giving us a look at the variety and commonalities of this musical tradition that has remained vibrant across time and space.

A week later, with the organization and vision of Zachary Edinger of Congregation Shearith Israel there was a monumental gathering of hazzanim from communities in Europe and the Americas, each singing a part of the classic Azharot [liturgical poems recited on Shabuot]. We also had a panel of authors—Laura Leibman, Stanley Mirvis and Hillit Surowitz-Israel—with new books coming out right now about the Jews of the Caribbean. COVID may have changed the nature of the book tour, but at least we were able to get these authors together for a serious conversation about race, religion and the writing of history.

On the one hand, none of these events could substitute for the energy, the serendipity and sociality of a conference, the casual conversation during the coffee breaks or the fabulous tip we get from a random panel we happen to stumble on.

But, on the other hand, we got something else: we got the people who could not make it for whatever reason—money, disability, life itself! We got to connect with people across oceans and time zones and share our ideas and passions through these little boxes.

As I was writing this piece, I was interrupted by another sort of Diasporic reality. Our house cleaner received a call from Mexico; her cousin, with whom she shared her childhood in a small village near Puebla and who was her next-door neighbor and worked as a nurse, passed away from COVID-19. This comes on the heels of losing her uncle, a restauranteur in Queens, and an aunt in Minnesota to the disease.

It was too much to bear. She went home to cry and to feel the loneliness that comes from living so far away from people you are so close to; she was hit with the pain of living in a world where you can receive a call on your cell phone from a small village in rural Mexico but can’t fly back home for a funeral, can’t mourn with the people you love.

I cannot wait for life in the corona-Zoomisphere to end. We are all interconnected with great ease thanks to phones and texts and FaceTime and Zoom, but it is the social capital we have invested in each other over years and years, hours and hours of shared meals, walks, time in the classroom, playground, at the office or factory that allows for the digital connections to be humanly possible. How much longer until we are only running on fumes, grasping at connections that fray because we have lost the human touch, the smell and sounds of empty space between us, of the shades of light that paint us as we sit on a park bench or walk beneath a canopy of trees?

I look forward to re-entering shared spaces, but I am quite certain that we will hold on to the opportunities afforded to us by virtual connections. I hope that this can get us to a place where the virtual can enhance the lived-in reality.

On the one hand, none of these events could substitute for the energy, the serendipity and sociality of a conference, the casual conversation during the coffee breaks or the fabulous tip we get from a random panel we happen to stumble on.

But, on the other hand, we got something else: we got the people who could not make it for whatever reason—money, disability, life itself! We got to connect with people across oceans and time zones and share our ideas and passions through these little boxes.

As I was writing this piece, I was interrupted by another sort of Diasporic reality. Our house cleaner received a call from Mexico; her cousin, with whom she shared her childhood in a small village near Puebla and who was her next-door neighbor and worked as a nurse, passed away from COVID-19. This comes on the heels of losing her uncle, a restauranteur in Queens, and an aunt in Minnesota to the disease.

It was too much to bear. She went home to cry and to feel the loneliness that comes from living so far away from people you are so close to; she was hit with the pain of living in a world where you can receive a call on your cell phone from a small village in rural Mexico but can’t fly back home for a funeral, can’t mourn with the people you love.

I cannot wait for life in the corona-Zoomisphere to end. We are all interconnected with great ease thanks to phones and texts and FaceTime and Zoom, but it is the social capital we have invested in each other over years and years, hours and hours of shared meals, walks, time in the classroom, playground, at the office or factory that allows for the digital connections to be humanly possible. How much longer until we are only running on fumes, grasping at connections that fray because we have lost the human touch, the smell and sounds of empty space between us, of the shades of light that paint us as we sit on a park bench or walk beneath a canopy of trees?

I look forward to re-entering shared spaces, but I am quite certain that we will hold on to the opportunities afforded to us by virtual connections. I hope that this can get us to a place where the virtual can enhance the lived-in reality.

On July 27, 2020, I taught a class—nothing unusual for a professor in that. Except that during this class, on the period from the anti-Jewish riots of 1391 to the expulsion of the Jews in 1492, 500 people from Chile, Panama, Mexico, Miami, Tetuán and Caracas, to name just a few of the places, joined me through the Zoomisphere as I sat in my basement, my bookshelf behind me, wearing a suit (but keeping my sandals on). I was invited to teach this class by Rabbi Marcos Metta, a dynamic rabbi in Mexico City whom I had the honor to meet on a research trip to that sprawling megalopolis a few years back. I had taught at his synagogue in the leafy suburb of Lomas and had met a diverse, curious crowd of adult learners as part of his innovative Beit Midrash, Majón Torá veDaat. From the questions I was asked I could tell that the people on the call from all over the Americas were smart, well-educated and passionate participants. In signing on to this class about medieval Spain, these participants were strengthening their Diasporic ties while linking themselves back in time to a crucial and often misunderstood chapter in their communal formation. And as the president of FeSeLa (Federación Sefaradi Latinoamericana), one of the class’ organizer’s said, this was the first time that so many communities were able to share this singular experience.

But…

But I missed hearing their voices, seeing their faces, being in the same room sharing pastries and coffee after the lecture, joining a minyan for arbit [evening prayer] right after the class, listening to a mourner say the Kaddish [prayer of mourning] for their loved one, noticing who joined and who sat out this act of public piety.

I missed the little things, missed people in the flesh, even missed the mishaps along the way: the traffic on the way to the community center, the rain that keeps people away.

But…

But with all my sense of loss, I must also admit that this Zoom thing is pretty miraculous because it allows Diasporic communities to highlight and live their connections “in real time.”

For centuries different Diasporic groups maintained their identity despite their geographic and political separations through trading networks, bonds of marriage and shared customs and religious beliefs. But these ties were maintained through the traffic in letters, goods, money and people. It also took patience for that letter, or that shipment of pepper, or the groom to arrive, and so it took imagination to maintain that sense of cohesiveness that linked people across the seas and mountains and empires that separated one member of the group from another. Zoom allows us to create and keep those bonds immediately and all at the same time.

Here’s another example. This spring, in collaboration with the American Sephardi Federation, I was involved in Zoom events linking scholars, hazzanim [cantors] and passionate members of the western Sephardic diaspora. These events came out of a landmark international research conference that had been scheduled for early May, called the Global Nação, referring to the global network of trade and faith that linked the western Sephardim from Amsterdam to Curacao to Livorno to Jamaica to New Amsterdam.

The conference was part of the Diasporas Project at the Rabbi Arthur Schneir Program for International Affairs, a multi-faceted series of events exploring the connections that cross political and geographic divides in our globalized world.

We obviously could not have the conference, but we decided to host a mix of communal and scholarly programs. The first was a musical tour of cantorial music with hazzanim from Tuscany, Amsterdam, Bayonne, London and New York, giving us a look at the variety and commonalities of this musical tradition that has remained vibrant across time and space.

A week later, with the organization and vision of Zachary Edinger of Congregation Shearith Israel there was a monumental gathering of hazzanim from communities in Europe and the Americas, each singing a part of the classic Azharot [liturgical poems recited on Shabuot]. We also had a panel of authors—Laura Leibman, Stanley Mirvis and Hillit Surowitz-Israel—with new books coming out right now about the Jews of the Caribbean. COVID may have changed the nature of the book tour, but at least we were able to get these authors together for a serious conversation about race, religion and the writing of history.

But…

But I missed hearing their voices, seeing their faces, being in the same room sharing pastries and coffee after the lecture, joining a minyan for arbit [evening prayer] right after the class, listening to a mourner say the Kaddish [prayer of mourning] for their loved one, noticing who joined and who sat out this act of public piety.

I missed the little things, missed people in the flesh, even missed the mishaps along the way: the traffic on the way to the community center, the rain that keeps people away.

But…

But with all my sense of loss, I must also admit that this Zoom thing is pretty miraculous because it allows Diasporic communities to highlight and live their connections “in real time.”

For centuries different Diasporic groups maintained their identity despite their geographic and political separations through trading networks, bonds of marriage and shared customs and religious beliefs. But these ties were maintained through the traffic in letters, goods, money and people. It also took patience for that letter, or that shipment of pepper, or the groom to arrive, and so it took imagination to maintain that sense of cohesiveness that linked people across the seas and mountains and empires that separated one member of the group from another. Zoom allows us to create and keep those bonds immediately and all at the same time.

Here’s another example. This spring, in collaboration with the American Sephardi Federation, I was involved in Zoom events linking scholars, hazzanim [cantors] and passionate members of the western Sephardic diaspora. These events came out of a landmark international research conference that had been scheduled for early May, called the Global Nação, referring to the global network of trade and faith that linked the western Sephardim from Amsterdam to Curacao to Livorno to Jamaica to New Amsterdam.

The conference was part of the Diasporas Project at the Rabbi Arthur Schneir Program for International Affairs, a multi-faceted series of events exploring the connections that cross political and geographic divides in our globalized world.

We obviously could not have the conference, but we decided to host a mix of communal and scholarly programs. The first was a musical tour of cantorial music with hazzanim from Tuscany, Amsterdam, Bayonne, London and New York, giving us a look at the variety and commonalities of this musical tradition that has remained vibrant across time and space.

A week later, with the organization and vision of Zachary Edinger of Congregation Shearith Israel there was a monumental gathering of hazzanim from communities in Europe and the Americas, each singing a part of the classic Azharot [liturgical poems recited on Shabuot]. We also had a panel of authors—Laura Leibman, Stanley Mirvis and Hillit Surowitz-Israel—with new books coming out right now about the Jews of the Caribbean. COVID may have changed the nature of the book tour, but at least we were able to get these authors together for a serious conversation about race, religion and the writing of history.

On the one hand, none of these events could substitute for the energy, the serendipity and sociality of a conference, the casual conversation during the coffee breaks or the fabulous tip we get from a random panel we happen to stumble on.

But, on the other hand, we got something else: we got the people who could not make it for whatever reason—money, disability, life itself! We got to connect with people across oceans and time zones and share our ideas and passions through these little boxes.

As I was writing this piece, I was interrupted by another sort of Diasporic reality. Our house cleaner received a call from Mexico; her cousin, with whom she shared her childhood in a small village near Puebla and who was her next-door neighbor and worked as a nurse, passed away from COVID-19. This comes on the heels of losing her uncle, a restauranteur in Queens, and an aunt in Minnesota to the disease.

It was too much to bear. She went home to cry and to feel the loneliness that comes from living so far away from people you are so close to; she was hit with the pain of living in a world where you can receive a call on your cell phone from a small village in rural Mexico but can’t fly back home for a funeral, can’t mourn with the people you love.

I cannot wait for life in the corona-Zoomisphere to end. We are all interconnected with great ease thanks to phones and texts and FaceTime and Zoom, but it is the social capital we have invested in each other over years and years, hours and hours of shared meals, walks, time in the classroom, playground, at the office or factory that allows for the digital connections to be humanly possible. How much longer until we are only running on fumes, grasping at connections that fray because we have lost the human touch, the smell and sounds of empty space between us, of the shades of light that paint us as we sit on a park bench or walk beneath a canopy of trees?

I look forward to re-entering shared spaces, but I am quite certain that we will hold on to the opportunities afforded to us by virtual connections. I hope that this can get us to a place where the virtual can enhance the lived-in reality.

On the one hand, none of these events could substitute for the energy, the serendipity and sociality of a conference, the casual conversation during the coffee breaks or the fabulous tip we get from a random panel we happen to stumble on.

But, on the other hand, we got something else: we got the people who could not make it for whatever reason—money, disability, life itself! We got to connect with people across oceans and time zones and share our ideas and passions through these little boxes.

As I was writing this piece, I was interrupted by another sort of Diasporic reality. Our house cleaner received a call from Mexico; her cousin, with whom she shared her childhood in a small village near Puebla and who was her next-door neighbor and worked as a nurse, passed away from COVID-19. This comes on the heels of losing her uncle, a restauranteur in Queens, and an aunt in Minnesota to the disease.

It was too much to bear. She went home to cry and to feel the loneliness that comes from living so far away from people you are so close to; she was hit with the pain of living in a world where you can receive a call on your cell phone from a small village in rural Mexico but can’t fly back home for a funeral, can’t mourn with the people you love.

I cannot wait for life in the corona-Zoomisphere to end. We are all interconnected with great ease thanks to phones and texts and FaceTime and Zoom, but it is the social capital we have invested in each other over years and years, hours and hours of shared meals, walks, time in the classroom, playground, at the office or factory that allows for the digital connections to be humanly possible. How much longer until we are only running on fumes, grasping at connections that fray because we have lost the human touch, the smell and sounds of empty space between us, of the shades of light that paint us as we sit on a park bench or walk beneath a canopy of trees?

I look forward to re-entering shared spaces, but I am quite certain that we will hold on to the opportunities afforded to us by virtual connections. I hope that this can get us to a place where the virtual can enhance the lived-in reality.