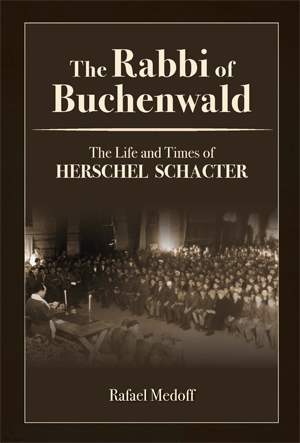

On Sunday, May 2, 2021, over 500 people on Zoom attended the book launch of The Rabbi of Buchenwald: The Life and Times of Herschel Schacter, written by Dr. Rafael Medoff and published by YU Press.

Dr. Medoff is the founding director of The David S. Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies, based in Washington, D.C. He is the author of more than twenty books on American Jewish history, Zionism and the Holocaust.

The event was sponsored by the Emil A. and Jenny Fish Center for Holocaust & Genocide Studies.

Rabbi Dr. Ari Berman, President of Yeshiva University, and Rabbi Yaakov Glasser, David Mitzner Dean of the Center for the Jewish Future, spoke eloquently of the example of compassion and action set by Rabbi Herschel Schacter’s life, with Dr. Berman emphasizing that what the book does best is “inspire us to become this kind of person.”

Rabbi Herschel Schacter’s children, Rabbi Dr. Jacob J. Schacter (University Professor of Jewish History and Jewish Thought and Senior Scholar at the Center for the Jewish Future) and Miriam Schacter ’75W, LCSW (a psychoanalyst in private practice and a faculty member of Yeshivat Chovevei Torah Rabbinical School), gave a more intimate picture of the man who, as their mother, Pnina, described him, was the man who “went to help the Jews.”

Miriam recounted multiple stories of people she had met who told her, time and again, how her father had saved their lives and set them on new paths, and as she grew older, she more fully realized why he had been able to do what he did: “He had stepped up and made life better based on the deep convictions he held,” all of which began with Buchenwald.

Discussing the themes of the book and the significance of its title, Dr. Medoff explained that the ten weeks Rabbi Schacter spent as a U.S. army chaplain in liberated Buchenwald in 1945 became “the transformative experience of his life.” As a result of what he saw, Rabbi Schacter devoted the rest of his professional life to Jewish communal service, included leadership of organizations dedicated to Soviet Jewry and Religious Zionism, and serving as chairman of the Conference of Presidents of Major American Jewish Organizations. He was the first Orthodox rabbi to reach that position.

Rabbi Schacter was also deeply committed to promoting Modern Orthodoxy. Dr. Medoff described him as one of the unheralded pioneers of Orthodox outreach, as he and his wife, Pnina, influenced many Jewish teens in the Bronx to become religiously observant in the 1950s.

Later, in the 1980s and 1990s, Rabbi Schacter, as the head of rabbinic placement for the Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary (from which he graduated in 1941 after graduating from Yeshiva College in 1938), helped hundreds of young rabbis launch their careers and strengthen local Orthodox communities throughout North America.

But clearly, the most affecting story told during the event was Rabbi Schacter’s own as he spoke in an audio recording played for the audience about the day he entered what he called “the gates of Hell”:

On Sunday, May 2, 2021, over 500 people on Zoom attended the book launch of The Rabbi of Buchenwald: The Life and Times of Herschel Schacter, written by Dr. Rafael Medoff and published by YU Press.

Dr. Medoff is the founding director of The David S. Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies, based in Washington, D.C. He is the author of more than twenty books on American Jewish history, Zionism and the Holocaust.

The event was sponsored by the Emil A. and Jenny Fish Center for Holocaust & Genocide Studies.

Rabbi Dr. Ari Berman, President of Yeshiva University, and Rabbi Yaakov Glasser, David Mitzner Dean of the Center for the Jewish Future, spoke eloquently of the example of compassion and action set by Rabbi Herschel Schacter’s life, with Dr. Berman emphasizing that what the book does best is “inspire us to become this kind of person.”

Rabbi Herschel Schacter’s children, Rabbi Dr. Jacob J. Schacter (University Professor of Jewish History and Jewish Thought and Senior Scholar at the Center for the Jewish Future) and Miriam Schacter ’75W, LCSW (a psychoanalyst in private practice and a faculty member of Yeshivat Chovevei Torah Rabbinical School), gave a more intimate picture of the man who, as their mother, Pnina, described him, was the man who “went to help the Jews.”

Miriam recounted multiple stories of people she had met who told her, time and again, how her father had saved their lives and set them on new paths, and as she grew older, she more fully realized why he had been able to do what he did: “He had stepped up and made life better based on the deep convictions he held,” all of which began with Buchenwald.

Discussing the themes of the book and the significance of its title, Dr. Medoff explained that the ten weeks Rabbi Schacter spent as a U.S. army chaplain in liberated Buchenwald in 1945 became “the transformative experience of his life.” As a result of what he saw, Rabbi Schacter devoted the rest of his professional life to Jewish communal service, included leadership of organizations dedicated to Soviet Jewry and Religious Zionism, and serving as chairman of the Conference of Presidents of Major American Jewish Organizations. He was the first Orthodox rabbi to reach that position.

Rabbi Schacter was also deeply committed to promoting Modern Orthodoxy. Dr. Medoff described him as one of the unheralded pioneers of Orthodox outreach, as he and his wife, Pnina, influenced many Jewish teens in the Bronx to become religiously observant in the 1950s.

Later, in the 1980s and 1990s, Rabbi Schacter, as the head of rabbinic placement for the Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary (from which he graduated in 1941 after graduating from Yeshiva College in 1938), helped hundreds of young rabbis launch their careers and strengthen local Orthodox communities throughout North America.

But clearly, the most affecting story told during the event was Rabbi Schacter’s own as he spoke in an audio recording played for the audience about the day he entered what he called “the gates of Hell”:

The most unforgettable day in my life was April 11, 1945. It was on that day that as a young American army chaplain, I served with frontline troops across Europe and then precisely on that day came upon the infamous, notorious Buchenwald concentration camp.

I had heard nothing of Buchenwald until that day. It was only my sad experience to have seen, to have participated in the ravages of war, to have seen cities laid waste and homes destroyed and human beings crushed.

But especially do I consider it a privilege, tragic and grievous though it was, to have come face to face with the stark, bitter, sordid reality of Jewish tragedy.

As I mentioned a moment ago, I came upon this hellhole called Buchenwald within a matter of hours after the first columns of American tanks rolled through and liberated that dungeon on the face of this Earth.

I do indeed consider it a privilege, tragic, sad, to have been among those who literally opened the gates of Hell.

The crematoria. I saw hundreds of human bodies strewn in front of the ovens that were still hot, the smoke still curling upwards, waiting, waiting to be shoveled into the furnaces.

How can any human being ever forget such a sight?

I stood there in front of those hot ovens, my eyes riveted—[garbled] I must tell you that whenever I even attempt to repeat this story, to relive that moment, it is exceedingly difficult to do so.

I ran to seek out Jews, to find that Jews were still alive, and indeed there they were, in a long series of low barracks. I ran into one after another, and there again, no matter what we have seen or heard, there simply are no words in the human vocabulary that can even remotely attempt to describe the horrors, the brutal, inhuman horrors, that were perpetrated against our people.

Within this huge Buchenwald camp, there was one area that was called das kleine Lager, the small camp, that was reserved especially for the brutal treatment of Jews. I went into those barracks and there I saw just raw planks of wood shelves on which were strewn scraggly, stinking, straw sacks, and there they were looking down at me, men, a few boys—there were no women in Buchenwald—but I will never forget those eyes: haunted with fear, half crazed, emaciated, more dead than alive.

Spontaneously, intuitively, I felt the only language that I could speak that most of them would understand was Yiddish, and I called out “Sholem aleichem Yidn, ir zent fray”: You are free, the war is over.

And there they were looking out at me through incredulous eyes.

But again, I can't continue. I could go on and on, but from that moment I must tell you that my life changed—the impact of that experience was enormous on the whole course of my career.

The Rabbi of Buchenwald is published with the support of the Michael Scharf Publication Trust of the Yeshiva University Press and the Fish Center, and distributed by Ktav Publishing House.