Jan 18, 2021 By: yunews

Dr. Shay Pilnik

Dr. Shay PilnikDr. Pilnik, thank you for taking the time to share your thoughts about and plans for the Fish Center. What drew you take the director’s position?

I have been in Holocaust education for over a decade. And when I saw the position at Yeshiva, I thought that the insights I had gained from my work could be applied to a new institution to improve the field on a national level and international level. That's the primary reason why I came, and I'm very excited to say that during the past year I have worked with my colleagues to build the foundations of the Center and prepare for the grand launch of our graduate programs. I must also say that I was drawn to do this work through the vision of Emil Fish.Speak about that a bit, if you could.

Emil Fish is a Holocaust survivor who survived Bergen-Belsen as a child. We’re fortunate that the philanthropist behind the Center is somebody who is directly touched by the subject that we’re studying. He is the real visionary here. To a great extent, Holocaust education and Holocaust studies have been propelled by Holocaust survivors, which was my experience in Milwaukee. These volunteers insisted that what happened to them personally marks a historic moment in the annals of human civilization and has to be taught, especially as, for younger generations, it’s becoming both in terms of time and space a more and more distant event. Going back to Emil's vision, he realized that because the survivors holding up the edifice of Holocaust education are passing day by day, the field has to be professionalized. And here we come to both the mission of the Center and Emil’s vision, which is to train the new cadre of educators in Holocaust education and genocide studies, giving them the tools to guarantee the professional integrity of the field.What challenges does this new cadre face?

There are several, but the primary one may be the one that sounds a bit absurd: to insist upon the Holocaust as a Jewish experience anchored in the history of the Shoah. The Holocaust does teach us many universal lessons, but the way the Holocaust is taught in the United States creates the danger that over time the subject can become marginalized and sidelined if we do not assert that the event is significant because the Holocaust was the only genocide in history with the intent of wiping out every member of the Jewish people from the face of the earth—a unique and unprecedented event. That is why I want to design a program steeped in the experiences of the Jewish people before, during and after the Holocaust. With the Center located at a place like Yeshiva University, with its world-class faculty, we can really make the Fish Center into a beacon for Holocaust and genocide studies. And the graduates of this program are going to be the new generation of teachers and leaders better qualified to teach and ready to defend the field’s integrity.How have you designed the proposed program to take advantage of what the University offers in terms of its programs and people?

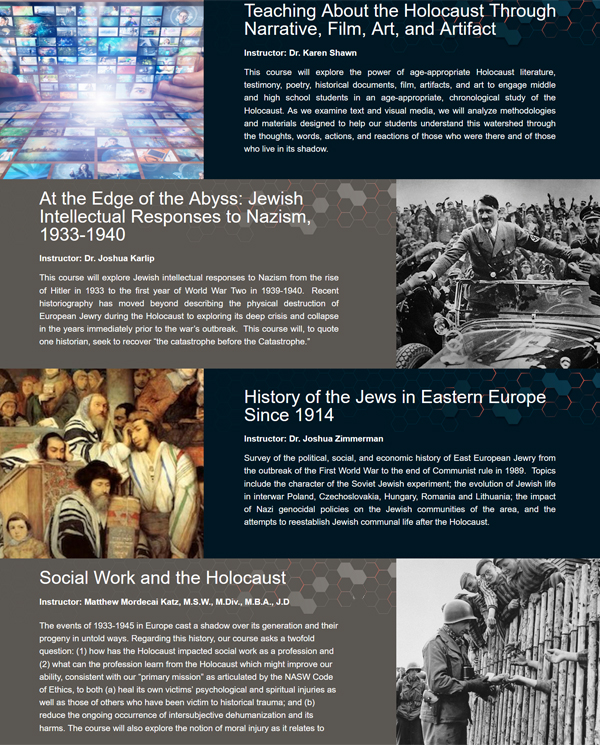

When you realize that the Holocaust is a watershed event in the history of humanity, you must also observe its impact on our lives. The interdisciplinary nature of our proposed program, and the interdisciplinary sophistication of our faculty, exactly addresses that issue. I envisage a curriculum that shows students that to study the Holocaust is not only to understand the chronology of events but also to understand the impact of the Holocaust on the fields of literature, law, film studies, memory studies, social work and theology, to name just a few. A good example of this are the four Fish Center-affiliated courses being offered this spring: Social Work and the Holocaust (Matthew Katz), History of the Jews in Eastern Europe Since 1914 (Dr. Joshua Zimmerman), At the Edge of the Abyss: Jewish Intellectual Responses to Nazism, 1933-1940 (Dr. Josh Karlip) and Teaching About the Holocaust Through Narrative, Film, Art, and Artifact (Dr. Karen Shawn). Four instructors from four YU schools meeting at the intersection of multiple areas of study: this is the essence of what the Fish Center wants to offer.