Nov 17, 2010 By: libraryblog

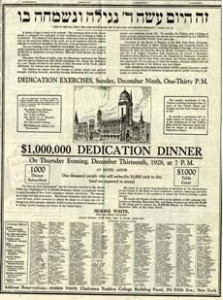

Large Hebrew letters boldly crowned Yeshiva’s advertisement in the New York Times on November 8, 1928, an early instance of Hebrew characters gracing that venerable publication:

"זה היום עשה ד’ נגילה ונשמחה בו" -

‘”This is the day that the Lord hath made: let us be glad and rejoice thereon.’—Psalms 118:24.” A similar ad in the Yiddish press proclaimed:

"והבית הזה יהיה עליון..." -

And this House shall be elevated - Kings I, 9:8.

Both ads announced the Chanukat HaBayit, the dedication, of the new Yeshiva College building, the first step in the creation of the Washington Heights campus. The dedication ceremonies were scheduled for December 9, 1928, followed by a Chanuka banquet four days later. The ads, and the Biblical verses they quote, invoke the Temple, the ancient Bet Mikdash in Jerusalem, in describing the new building. The choice of Chanuka for the dedication ceremonies and dinner was deliberate and symbolic. As the ad states, “Chanukah, the Feast of Lights, when the Maccabees rededicated the Temple after the historic victory over their Greek adversaries, will witness the dedication of a new Temple devoted to the service of God, the study of the Torah, Jewish philosophy, the sciences and American institutions.”

The inauguration of the magnificent new edifice marked the move uptown from the impoverished, overcrowded, immigrant neighborhood of the Lower East Side to the then bucolic Washington Heights. It also launched a new era in the life of the institution - the addition of a new college of liberal arts and sciences to the Yeshiva.

The ornate Moorish Revival structure on Amsterdam Avenue, completed in 1928, can be viewed whimsically as Yeshiva’s bar-mitzva present to itself. Thirteen years earlier, the 1915 Chanuka dinner had celebrated a different milestone in the growth of the institution, the dedication of a new home in a small refurbished building on Montgomery Street. The 1915 event is Yeshiva’s earliest Chanuka dinner on record. It witnessed the long-planned union of two pioneering American Jewish institutions, Yeshiva Etz Chaim (founded 1886) and the Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary (founded 1897). The dedication also served as the inauguration of Rabbi Dr. Bernard Revel as Rosh Yeshiva and President of the institution, and heralded the establishment of the Talmudical Academy high school, a novel educational concept which offered traditional Jewish studies along with a New York State Regents general studies curriculum.

Harry Fischel, realtor, well-known philanthropist, and Chairman of the Building Committee, spoke at the 1915 dedication. He compared Yeshiva’s growth to the lighting of the Chanuka candles, where a candle is added every night of the holiday: “in everything that is Holy, we should always increase and never decrease, … so with our Yeshivah, while we are beginning with a comparatively small building, yet we hope that it will grow in strength and usefulness from year to year until we achieve the great result for which we are aiming, and it is our hope, that like a seed which is carefully planted in fertile soil, this institution will grow into a flourishing plant, whose fruit will refresh and revive Judaism in the whole of the United States.”

The building on Montgomery Street and the Chanuka dinner at the opening were modest. One observer commented on the “long rough tables … unwieldy plates and rusty flatware” at the 1915 dinner. Typical fare at Yeshiva “simchas” at the time was herring and schnaps. By Chanuka of 1928, both the menu and venue had changed dramatically. The kosher catering at the elegant Hotel Astor in midtown Manhattan, was lavish. Even the handsome printed menu, in the shape of a book, testified to Yeshiva’s new status.

The theme of the Chanuka dinner of 1928 was, in the words of the dinner chairman, Morris White, “to dine for a divine purpose” – to transform the mundane into the sacred. So, too, the Yeshiva College building utilized ordinary brick and mortar to honor and glorify Torah. The new building, and the proposed campus, would fulfill Yeshiva’s dual mission. The school, in the words of the Yiddish ad, would be both “the most beautiful home for Torah ever seen in Exile,” a yeshiva on par with Eastern European yeshivas, and, a college with “general studies … under the influence and in the spirit of our holy Torah.” From the start, therefore, the planners were determined to create a distinctive edifice whose unique design would embody its divine function.

When the Building Committee initially began planning the campus in 1924, Harry Fischel proclaimed that Yeshiva needed a “Betsalel,” a reference to the master builder of the Mishkan, the Tabernacle, in the Bible. “Betsalel” initially appeared in the form of Joshua [O.G.] Tabatchnik, “a young architect who lately landed from Palestine.” Tabatchnik had studied architecture in Odessa, and with Boris Schatz at the Bezalel School in Jerusalem. He designed Bet Ha-Dekel, (the Palm Tree house), a Tel-Aviv landmark, and the palatial Diskin Orphan Home in Jerusalem, among other projects.

Tabatchnik, whose plans for the campus were unveiled at the 1924 Chanuka dinner, arrived in New York to introduce, according to the New York Times, innovations in structural engineering and “a new style of typically Hebraic architecture.” Fischel worked with Tabatchnik on the proposed new buildings. Renderings of Tabatchnik’s plan, which never came to fruition, are housed in the Yeshiva University Archives. The promotional literature for Tabatchnik’s design discusses influences ranging from Solomon’s Temple to Patrick Geddes and Frank Mears’ early 1920s plans for the Hebrew University campus on Mt. Scopus, Jerusalem.

Large Hebrew letters boldly crowned Yeshiva’s advertisement in the New York Times on November 8, 1928, an early instance of Hebrew characters gracing that venerable publication:

"זה היום עשה ד’ נגילה ונשמחה בו" -

‘”This is the day that the Lord hath made: let us be glad and rejoice thereon.’—Psalms 118:24.” A similar ad in the Yiddish press proclaimed:

"והבית הזה יהיה עליון..." -

And this House shall be elevated - Kings I, 9:8.

Both ads announced the Chanukat HaBayit, the dedication, of the new Yeshiva College building, the first step in the creation of the Washington Heights campus. The dedication ceremonies were scheduled for December 9, 1928, followed by a Chanuka banquet four days later. The ads, and the Biblical verses they quote, invoke the Temple, the ancient Bet Mikdash in Jerusalem, in describing the new building. The choice of Chanuka for the dedication ceremonies and dinner was deliberate and symbolic. As the ad states, “Chanukah, the Feast of Lights, when the Maccabees rededicated the Temple after the historic victory over their Greek adversaries, will witness the dedication of a new Temple devoted to the service of God, the study of the Torah, Jewish philosophy, the sciences and American institutions.”

The inauguration of the magnificent new edifice marked the move uptown from the impoverished, overcrowded, immigrant neighborhood of the Lower East Side to the then bucolic Washington Heights. It also launched a new era in the life of the institution - the addition of a new college of liberal arts and sciences to the Yeshiva.

The ornate Moorish Revival structure on Amsterdam Avenue, completed in 1928, can be viewed whimsically as Yeshiva’s bar-mitzva present to itself. Thirteen years earlier, the 1915 Chanuka dinner had celebrated a different milestone in the growth of the institution, the dedication of a new home in a small refurbished building on Montgomery Street. The 1915 event is Yeshiva’s earliest Chanuka dinner on record. It witnessed the long-planned union of two pioneering American Jewish institutions, Yeshiva Etz Chaim (founded 1886) and the Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary (founded 1897). The dedication also served as the inauguration of Rabbi Dr. Bernard Revel as Rosh Yeshiva and President of the institution, and heralded the establishment of the Talmudical Academy high school, a novel educational concept which offered traditional Jewish studies along with a New York State Regents general studies curriculum.

Harry Fischel, realtor, well-known philanthropist, and Chairman of the Building Committee, spoke at the 1915 dedication. He compared Yeshiva’s growth to the lighting of the Chanuka candles, where a candle is added every night of the holiday: “in everything that is Holy, we should always increase and never decrease, … so with our Yeshivah, while we are beginning with a comparatively small building, yet we hope that it will grow in strength and usefulness from year to year until we achieve the great result for which we are aiming, and it is our hope, that like a seed which is carefully planted in fertile soil, this institution will grow into a flourishing plant, whose fruit will refresh and revive Judaism in the whole of the United States.”

The building on Montgomery Street and the Chanuka dinner at the opening were modest. One observer commented on the “long rough tables … unwieldy plates and rusty flatware” at the 1915 dinner. Typical fare at Yeshiva “simchas” at the time was herring and schnaps. By Chanuka of 1928, both the menu and venue had changed dramatically. The kosher catering at the elegant Hotel Astor in midtown Manhattan, was lavish. Even the handsome printed menu, in the shape of a book, testified to Yeshiva’s new status.

The theme of the Chanuka dinner of 1928 was, in the words of the dinner chairman, Morris White, “to dine for a divine purpose” – to transform the mundane into the sacred. So, too, the Yeshiva College building utilized ordinary brick and mortar to honor and glorify Torah. The new building, and the proposed campus, would fulfill Yeshiva’s dual mission. The school, in the words of the Yiddish ad, would be both “the most beautiful home for Torah ever seen in Exile,” a yeshiva on par with Eastern European yeshivas, and, a college with “general studies … under the influence and in the spirit of our holy Torah.” From the start, therefore, the planners were determined to create a distinctive edifice whose unique design would embody its divine function.

When the Building Committee initially began planning the campus in 1924, Harry Fischel proclaimed that Yeshiva needed a “Betsalel,” a reference to the master builder of the Mishkan, the Tabernacle, in the Bible. “Betsalel” initially appeared in the form of Joshua [O.G.] Tabatchnik, “a young architect who lately landed from Palestine.” Tabatchnik had studied architecture in Odessa, and with Boris Schatz at the Bezalel School in Jerusalem. He designed Bet Ha-Dekel, (the Palm Tree house), a Tel-Aviv landmark, and the palatial Diskin Orphan Home in Jerusalem, among other projects.

Tabatchnik, whose plans for the campus were unveiled at the 1924 Chanuka dinner, arrived in New York to introduce, according to the New York Times, innovations in structural engineering and “a new style of typically Hebraic architecture.” Fischel worked with Tabatchnik on the proposed new buildings. Renderings of Tabatchnik’s plan, which never came to fruition, are housed in the Yeshiva University Archives. The promotional literature for Tabatchnik’s design discusses influences ranging from Solomon’s Temple to Patrick Geddes and Frank Mears’ early 1920s plans for the Hebrew University campus on Mt. Scopus, Jerusalem.

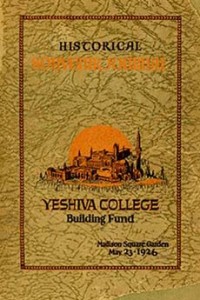

Tabatchnik’s plan was on the table only briefly, when, for unknown reasons, the Building Committee commissioned new plans from the architects Charles B. Meyers and Henry B. Herts. Both Meyers and Herts had previously designed synagogues. Herts in particular was known as “a specialist in Jewish architecture.” Their illustrations of the buildings and grounds were published in a souvenir journal, and presented to Yeshiva donors at the premiere of “Dedication of the Temple,” the third act of the opera ‘King Solomon’ by P.J. Engels. This performance, which featured Cantor Yossele Rosenblatt, was part of the “Million Dollar Music Festival,” a gala event held at Madison Square Garden in May 1926.

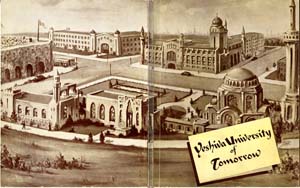

The illustrations, now part of the Yeshiva University Archives collection, depict an exotic campus. The proposed campus straddled Amsterdam Avenue. On the east side, the campus stretched from 186th to 188th streets and to Laurel Hill Terrace. The architectural drawings show a familiar building on the west side of Amsterdam Avenue, between 186th and 187th streets. This building, whose dedication was celebrated at the Chanuka dinner of 1928, is currently known as Zysman Hall. (See the forthcoming article in American Jewish History, “Yeshiva College and the New Jewish Architecture,” by Eitan Kastner)

Eleven days prior to the opening, the Yeshiva College building was the subject of a feature in the New York Times. The building also received extensive coverage in the general press. The Times article (Dec. 2, 1928 ) by Edward Jewell, entitled: “New Yeshiva College Unique in Architecture: Traditions of Old Semitic Art are Preserved and Adapted to Modern Demands,” quoted extensively from an interview with Herts: “The new structure, incorporating the latest expressions of practical modernity, offers embellishments that carry on, Mr. Herts believes, a Hebrew tradition hundreds, even thousands, of years old. Thus what we would seem to have in Yeshiva College is an authentic type of twentieth century Jewish architecture, yet compounded of numerous elements that derive specifically from a period covering several centuries B.C. and developed in various parts of the Old World in the opening centuries of the Christian era … [the building] appears to have risen spontaneously, even magically like the pleasure palace in one of the Arabian Nights tales that was reared ‘twixt sunset and dawn.’”

A mere ten months before the stock market crash of 1929, the guests and donors at the 1928 Chanukah Dedication dinner, sat in the splendid Astor Hotel ballroom, enjoyed the fine fare, and listened to the optimistic orations. Surrounded by exquisite décor they could not have been expected to imagine the economic catastrophe that would temporarily derail the planned growth of the rest of the campus, and forever doom the remainder of the Meyers and Herts’ design.

In the early years of the Great Depression that followed the 1929 crash, Yeshiva’s leaders continued to hope that they would be able to complete the campus. As the thirties progressed, the nation became more deeply mired in the depression. Donations to the institution dropped precipitously. Yeshiva nearly lost its new building to its creditors and was forced to sell the land on the east side of Amsterdam Avenue.

Tabatchnik’s plan was on the table only briefly, when, for unknown reasons, the Building Committee commissioned new plans from the architects Charles B. Meyers and Henry B. Herts. Both Meyers and Herts had previously designed synagogues. Herts in particular was known as “a specialist in Jewish architecture.” Their illustrations of the buildings and grounds were published in a souvenir journal, and presented to Yeshiva donors at the premiere of “Dedication of the Temple,” the third act of the opera ‘King Solomon’ by P.J. Engels. This performance, which featured Cantor Yossele Rosenblatt, was part of the “Million Dollar Music Festival,” a gala event held at Madison Square Garden in May 1926.

The illustrations, now part of the Yeshiva University Archives collection, depict an exotic campus. The proposed campus straddled Amsterdam Avenue. On the east side, the campus stretched from 186th to 188th streets and to Laurel Hill Terrace. The architectural drawings show a familiar building on the west side of Amsterdam Avenue, between 186th and 187th streets. This building, whose dedication was celebrated at the Chanuka dinner of 1928, is currently known as Zysman Hall. (See the forthcoming article in American Jewish History, “Yeshiva College and the New Jewish Architecture,” by Eitan Kastner)

Eleven days prior to the opening, the Yeshiva College building was the subject of a feature in the New York Times. The building also received extensive coverage in the general press. The Times article (Dec. 2, 1928 ) by Edward Jewell, entitled: “New Yeshiva College Unique in Architecture: Traditions of Old Semitic Art are Preserved and Adapted to Modern Demands,” quoted extensively from an interview with Herts: “The new structure, incorporating the latest expressions of practical modernity, offers embellishments that carry on, Mr. Herts believes, a Hebrew tradition hundreds, even thousands, of years old. Thus what we would seem to have in Yeshiva College is an authentic type of twentieth century Jewish architecture, yet compounded of numerous elements that derive specifically from a period covering several centuries B.C. and developed in various parts of the Old World in the opening centuries of the Christian era … [the building] appears to have risen spontaneously, even magically like the pleasure palace in one of the Arabian Nights tales that was reared ‘twixt sunset and dawn.’”

A mere ten months before the stock market crash of 1929, the guests and donors at the 1928 Chanukah Dedication dinner, sat in the splendid Astor Hotel ballroom, enjoyed the fine fare, and listened to the optimistic orations. Surrounded by exquisite décor they could not have been expected to imagine the economic catastrophe that would temporarily derail the planned growth of the rest of the campus, and forever doom the remainder of the Meyers and Herts’ design.

In the early years of the Great Depression that followed the 1929 crash, Yeshiva’s leaders continued to hope that they would be able to complete the campus. As the thirties progressed, the nation became more deeply mired in the depression. Donations to the institution dropped precipitously. Yeshiva nearly lost its new building to its creditors and was forced to sell the land on the east side of Amsterdam Avenue.

Despite the depression, both the prestige of the school and the size of the student body grew. For many years, the 1928 building, originally intended for the high school, followed in the footsteps of the tale of the Temple in Jerusalem, which miraculously expanded to include all who came; the lone building served all of Yeshiva’s needs. A vision of “Yeshiva University of Tomorrow,” a future campus based on the Meyers-Herts plan, appeared on the cover of a December 1945 dinner journal. This variation on a theme is the final known use of the plan. Eventually new buildings were added, although none were built in the Orientalist style of the original plan.

The Washington Heights campus, now the Wilf campus, is an eclectic mix of architectural styles. The Glueck Building, completed in 2009, is the most recent addition. The campus, and the school itself, have evolved in ways the founders could scarcely have imagined. The tradition of Yeshiva University’s Chanuka dinners continues to this day, an almost unbroken chain connecting today’s participants to their visionary counterparts at the 1915 event. Harry Fischel’s words nearly a century ago proved prophetic, and continue to be a fitting goal: “we should always increase and never decrease, … we hope that [Yeshiva] will grow in strength and usefulness from year to year.” Submitted by Shulamith Z. Berger